Oncology

Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Treating Midgut vs Non-Midgut Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) can have primary sites in the midgut or outside of the midgut, including tumors of unknown primary origin. Treatment outcomes may differ based on the primary tumor site. Researchers at the 2024 ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium reported real-world outcomes of patients with midgut and non-midgut NETs after receiving peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT).

Following this presentation, featured expert Jonathan R. Strosberg, MD, was interviewed by Conference Reporter Editor-in-Chief Tom Iarocci, MD. Dr Strosberg’s clinical perspectives on these findings are presented here.

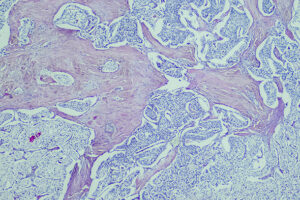

NETs are typically classified by primary tumor site, and each primary site has its own unique characteristics and different mutational patterns. Even if NETs from different primary sites look similar under a microscope, biologically, they are not the same tumors. Just like you would not expect a lung adenocarcinoma to be the same as a colorectal adenocarcinoma, you should not necessarily expect pancreatic NETs to be identical to midgut NETs in terms of clinical behavior, gene expression, or gene mutations. NETs in the midgut, which extends from the jejunum, through the ileum, and into the cecum, tend to have a high propensity for metastasizing (often to the mesentery and liver) and for producing serotonin (resulting in carcinoid syndrome). The reason we tend to use the word midgut rather than, say, small bowel is because the duodenum is biologically different from the rest of the small bowel, just as the distal colon, including the rectum, is biologically different from the proximal colon.

There are also NETs of unknown primary origin, as in other cancers. However, their frequency is decreasing as our imaging modalities become more sophisticated and our ability to identify primary tumors improves. For example, using dotatate positron emission tomography scans significantly increases our rate of detection of primary tumors. Sometimes you can also assume that you are dealing with a small intestinal primary tumor, even if you cannot directly see it, if the patient has a characteristic mesenteric tumor and carcinoid syndrome.

There are fewer systemic options for the management of midgut NETs compared with pancreatic NETs, where PRRT is potentially used in a later-line setting. PRRT is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for all gastroenteropancreatic NETs based on data from the NETTER-1 trial and on registry data from Rotterdam. The very small, randomized OCLURANDOM trial of 177Lu-dotatate (177Lu-octreotate) vs sunitinib in pancreatic NETs was underpowered for a comparison of the 2 arms, but the median progression-free survival (PFS) was clearly superior with 177Lu-dotatate, at 20.7 months vs 11 months with sunitinib.

Real-world data with 177Lu-dotatate in patients with midgut and non-midgut NETs were presented at the 2024 ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium (abstract 593). The data showed that patients with midgut NETs had a longer PFS than patients with non-midgut NETs following PRRT, and that is not surprising. Midgut NETs tend to be the slowest-growing NETs. Although there was no difference in PFS based on whether 177Lu-dotatate doses were reduced or delayed due to toxicity, this analysis had a very small number of patients, so there may have just been a lack of statistical power. I suspect that if you looked at larger numbers of patients, you would probably see statistically different outcomes with the lower dose, for various reasons. However, these data do reassure me that we may be able to reduce doses if necessary and still achieve relatively similar outcomes.

Baudin E, Walter TA, Beron A, et al. First multicentric randomized phase II trial investigating the antitumor efficacy of peptide receptor radionucleide therapy with 177Lutetium-octreotate (OCLU) in unresectable progressive neuroendocrine pancreatic tumor: results of the OCLURANDOM trial [abstract 8870]. Abstract presented at: European Society for Medical Oncology Congress 2022; September 9-13; Paris, France.

Brabander T, van der Zwan WA, Teunissen JJM, et al. Long-term efficacy, survival, and safety of [177Lu-DOTA0,Tyr3]octreotate in patients with gastroenteropancreatic and bronchial neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(16):4617-4624. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2743

Del Rivero J, Perez K, Kennedy EB, et al. Systemic therapy for tumor control in metastatic well-differentiated gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(32):5049-5067. doi:10.1200/JCO.23.01529

Lee H, Kipnis S, O’Brien S, Eads JR, Katona BW, Pryma DA. Real-world 177Lu-DOTATATE peptide receptor radionuclide therapy: treatment outcomes with dosing variations and in non-midgut neuroendocrine tumors [abstract 593]. Abstract presented at: 2024 American Society of Clinical Oncology Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium; January 18-20, 2024; San Francisco, CA.

Panarelli N, Tyryshkin K, Wong JJM, et al. Evaluating gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors through microRNA sequencing. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2019;26(1):47-57. doi:10.1530/ERC-18-0244

Strosberg JR, Caplin ME, Kunz PL, et al. 177Lu-Dotatate plus long-acting octreotide versus high‑dose long-acting octreotide in patients with midgut neuroendocrine tumours (NETTER-1): final overall survival and long-term safety results from an open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(2):e59]. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(12):1752-1763. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00572-6

This information is brought to you by Engage Health Media and is not sponsored, endorsed, or accredited by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.