Neurology

Multiple Sclerosis

Treatment Approaches to Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis

Overview

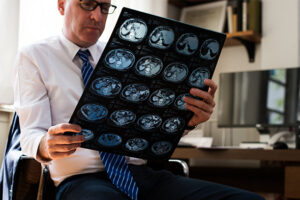

Highly effective anti-inflammatory therapies are available for treating patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS). The disease starts as an inflammatory process, which induces focal demyelinating lesions in the gray and white matter. This stage of the disease dominates in the relapsing phase and can be targeted by current anti-inflammatory treatments. Accumulation of inflammation peaks in the late relapsing and early progressive stage and then declines. Some data suggest that this process may be targeted by immune ablation and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Therapies for MS suppress inflammation and relapses, but their effectiveness for slowing disease progression and brain atrophy varies. Ocrelizumab, an anti-CD20 antibody, effectively reduced annualized relapse rate and disease progression, compared with interferon beta-1a, in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. A critical question is whether use of highly effective monoclonal antibodies, such as ocrelizumab, natalizumab, and alemtuzumab, at the onset of disease and would prevent later disease progression. In addition, the safety of all highly effective therapies should be continuously monitored because of the risks associated with impaired immune surveillance. Our featured experts in the field discuss treatment approaches to reduce relapses in patients with MS.

Q: What treatment approach would you use to reduce relapses in patients with MS?

Staley Brod, MD

|

|

“The issue among neurologists is deciding between immunomodulating agents (changing the behavior of cells) and immunosuppressive or immunoablative agents (getting rid of the cells in one way or another).”

I think that it depends a lot on the patient and the patient’s level of disease activity. There are 2 groups of prescribers: escalators, like myself, who tend to start with the more traditional “platform therapies,” and the induction mavens or accelerators, who use the more immunosuppressive or immunoablative drugs as a first-line agent. Most patients will do relatively well with the platform agents, at least for a period to time. To use the more advanced therapy, or more immunosuppressive agents, at the outset, the patient would have to be experiencing very active disease with multiple attacks—high burden of disease on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The issue among neurologists is deciding between immunomodulating agents (changing the behavior of cells) and immunosuppressive or immunoablative agents (getting rid of the cells in one way or another).

David A. Hafler, MD

|

|

“The critical question in MS is as follows: If you treat very early, before there are clinical symptoms, and continue treatment for 2 or 3 years, do we stop the disease and later entry into progressive disease?”

What we have learned from rheumatoid arthritis, where we can see the initial event, is that, if you use biologics such as anti–tumor necrosis factor alpha very early on, you can basically stop the disease and reset the immune system. The idea of allowing inflammation to occur in the central nervous system and allowing for potential permanent neurologic disability by using less effective drugs does not make sense. The critical question in MS is as follows: If you treat very early, before there are clinical symptoms, and continue treatment for 2 or 3 years, do we stop the disease and later entry into progressive disease? While this question will take perhaps decades to answer, it is hard to argue for allowing diffuse inflammation in the central nervous system. Thus, I would suggest early aggressive treatment. The issue that we have in MS is that we do not know when the disease really begins. So, the experiences with very early treatment of autoimmunity in psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis are hard to translate to MS, but the idea of using drugs historically because of their earlier use as first-line treatment is not logical to me.

On the other hand, I agree that if you have a patient with very mild disease, with no clinical symptoms, radiologically isolated syndrome at the present stage, it could be hard to argue for using certain treatments. The most benign treatment is glatiramer acetate in terms of long-term side effects. We have treated some patients with glatiramer acetate for 10 to 15 years, and they have done well, though many breakthrough with exacerbations. Many of those patients may have done very well with no treatment. It is very hard to predict the disease course in a patient with mild early disease, but the major question is, if we treat early and with the best immunosuppressants that we have, can we stop the disease from entering the progressive phase? What we are doing now at Yale is recommending ocrelizumab for patients who have a clear diagnosis of MS. If new biomarkers were developed based on single-RNA sequencing of cells in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood, can we develop a better understanding of what the drugs are actually doing? We want to treat patients very early, continue treatment for a specified number of years, and then discontinue treatment and see if we have stopped the disease. That is the direction we are trying to move toward.

“I think that patients who have an established diagnosis of MS and who have a form of MS that is inflammatory (ie, have a history of relapses or evidence of inflammatory disease based on MRI) should be treated with available disease-modifying agents.”

I think that patients who have an established diagnosis of MS and who have a form of MS that is inflammatory (ie, have a history of relapses or evidence of inflammatory disease based on MRI) should be treated with available disease-modifying agents. At the moment, we have about 15 of these medications to choose from, but there is a lack of biomarkers or other information to tell us exactly which medication is right for an individual patient. So, my approach is to take all of the information that I have at hand about the patient (eg, his or her clinical course to date, his or her MRI activity, changes over time if we have that information, his or her neurological examination, his or her own treatment preferences about things such as how aggressive he or she would like the treatment to be, what kinds of side effects he or she would like to avoid, his or her preferred route of administration) and then use all of that information to make a decision. I am influenced by growing data suggesting that there may be a role for the earlier use of so-called highly effective disease-modifying therapies, where the ability to reduce relapses to a greater degree might, in fact, have greater intermediate and long-term benefits than starting with less-efficacious drugs and then working up from there.

References

Calabresi PA. Advances in multiple sclerosis: from reduced relapses to remedies. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(1):10-12.

Dutta R, Trapp BD. Relapsing and progressive forms of multiple sclerosis: insights from pathology. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27(3):271–278.