Oncology

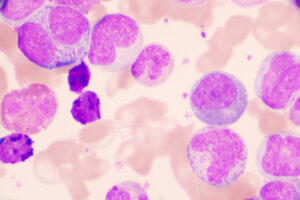

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

First-line Treatment of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Building on the Data

Overview

Our featured experts describe the latest data that guide decisions on initial therapy for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Increasingly, there is a move toward second-generation Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor therapy.

What is your current approach to first-line therapy for CLL?

John C. Byrd, MD

|

|

“In view of the ELEVATE-TN study data, along with data on zanubrutinib (another second-generation BTK inhibitor), I will now use acalabrutinib rather than ibrutinib in most frontline CLL treatment scenarios.”

For the patient with CLL who is at the point of requiring therapy, several factors stand out as we consider the treatment options, including the patient’s age and functional status, as well as the molecular features of the CLL. I consider the IGHV mutational status, the 17p deletion/TP53 mutation status, the presence of tetraploidy and other rare abnormalities, and the CLL genomics and the presence of uncommon mutations that might direct therapy. The presence of autoimmune complications or an extremely elevated white blood cell count are also informative. Today, I generally do not consider recommending frontline chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy, except in a few relatively rare scenarios.

Before the publication of the ELEVATE-TN study, a typical approach for me was to offer ibrutinib monotherapy. In view of the ELEVATE-TN study data, along with data on zanubrutinib (another second-generation BTK inhibitor), I will now use acalabrutinib rather than ibrutinib in most frontline CLL treatment scenarios. Clinical trials have shown favorable efficacy with acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab, and the ELEVATE-TN study demonstrated that the addition of obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib offered the advantage of progression-free survival and a nice trend toward overall survival in that group. For a patient in their 50s or 60s, or even in their 70s, in whom we are aiming to achieve a nice, deep response, I generally will use obinutuzumab with acalabrutinib.

In general, I stay away from venetoclax plus obinutuzumab as frontline therapy. An exception is in patients who have mechanical valves and need to be on warfarin long-term, or in those with an absolute contraindication to BTK inhibitor therapy. In these cases, I will use venetoclax plus obinutuzumab in the first line.

I think that the field has become polarized by the concept of time-limited therapy. The follow-up period in the CLL14 study is short, and the regimen is less effective in the high-risk, TP53-mutated group, and it is more difficult to apply because of the dose ramp-up and monitoring. Further, while the ELEVATE-TN study was not designed to evaluate stopping therapy, more and more anecdotal evidence suggests that patients who do stop BTK inhibitor–plus-obinutuzumab therapy after achieving minimal or low disease status can do very well for a long time and that they will respond again if retreated.

I tend to use acalabrutinib monotherapy in older patients who might have a contraindication to obinutuzumab and in those who live far away and do not want to have to come back and forth for the obinutuzumab therapy. In my view, venetoclax is mainly a second-line therapy. The venetoclax-plus-BTK inhibitor combinations that are currently in development will have high complete response rates, but whether they improve long-term outcomes is still unknown.

Ian W. Flinn, MD, PhD

|

|

“Many of my younger patients with CLL choose venetoclax plus obinutuzumab because they like the notion of time-limited therapy.”

I have not used frontline chemoimmunotherapy for CLL in years. All of my patients with CLL generally get either venetoclax plus obinutuzumab or a BTK inhibitor in the first line. I generally use BTK inhibitor monotherapy, without an anti-CD20 antibody. In patients with 17p deletions or TP53 mutations, I would start with a BTK inhibitor since this group does not do as well on venetoclax plus obinutuzumab.

Many of my younger patients with CLL choose venetoclax plus obinutuzumab because they like the notion of time-limited therapy. One might think that the benefit of time-limited therapy would be greater in older patients and thus preferred by this patient group, as they are more likely to experience the cardiovascular side effects associated with BTK inhibitors; however, older patients are often eager to avoid the logistical issues that go along with initiating venetoclax therapy. I think that younger people are more motivated to get off therapy, and, in that case, the hassle of having to go through the ramp-up and tumor lysis syndrome laboratory monitoring, and even debulking before treatment, tends to be more tolerable to them. I see a high uptake of venetoclax and obinutuzumab among younger patients and single-agent BTK inhibitor therapy among older patients.

I use primarily second-generation BTK inhibitors now, and I avoid ibrutinib in the vast majority of patients. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, I have avoided the anti-CD20 antibodies in patients who are receiving a BTK inhibitor, since we have not yet seen a survival advantage with this combination. The risk of infection is an important consideration right now. We know that anti-CD20 therapies may cause greater B-cell depletion and thereby increase the risk of COVID-19 compared with BTK inhibitors.

Jeff Sharman, MD

|

|

“I agree that there is an exquisitely small role for chemoimmunotherapy in frontline CLL treatment.”

I agree that there is an exquisitely small role for chemoimmunotherapy in frontline CLL treatment. And I agree with my colleagues on second-generation vs first-generation BTK inhibitors. Regarding venetoclax plus obinutuzumab, the ability to navigate the initiation of venetoclax may be influenced by patient resources, access to the treatment center, and other social factors, in addition to age. Some of these factors may support a decision to recommend BTK monotherapy rather than a fixed duration of obinutuzumab and venetoclax. Other factors to consider with venetoclax-plus-obinutuzumab therapy include kidney function, tumor bulk, and ultimate risk for tumor lysis syndrome. For instance, I may be more inclined to recommend a BTK inhibitor in a patient who might have a glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min/1.73m2 with bulky intra-abdominal nodes.

Regarding the use of an anti-CD20 antibody in combination with a BTK inhibitor, I have not been using anti-CD20 antibodies, primarily because of COVID-19. Although they are associated with progression-free survival benefits, they also have toxicities. If I were going to recommend an anti-CD20 antibody, it would likely be for a younger patient in whom I may already be inclined to use obinutuzumab and venetoclax based on other factors. I think that the progression-free survival benefits of anti-CD20 antibodies have increased over time, however, and, if not for COVID-19, I would likely be using these therapies a bit more frequently.

References

Al-Sawaf O, Zhang C, Lu T, et al. Minimal residual disease dynamics after venetoclax-obinutuzumab treatment: extended off-treatment follow-up from the randomized CLL14 study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(36):4049-4060. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.01181

Bewarder M, Stilgenbauer S, Thurner L, Kaddu-Mulindwa D. Current treatment options in CLL. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(10):2468. doi:10.3390/cancers13102468

Byrd JC, Woyach JA, Furman RR, et al. Acalabrutinib in treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2021;137(24):3327-3338. doi:10.1182/blood.2020009617

Mato AR, Barrientos JC, Ghosh N, et al. Prognostic testing and treatment patterns in chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of novel targeted therapies: results from the informCLL Registry. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(3):174-183.e3. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2019.10.009

Patel K, Pagel JM. Current and future treatment strategies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):69. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01054-w

Sharman JP, Egyed M, Jurczak W, et al. Acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil and obinutuzumab for treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (ELEVATE-TN): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1278-1291. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30262-2

Smolej L, Vodárek P, Écsiová D, Šimkovič M. Chemoimmunotherapy in the first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: dead yet, or alive and kicking? Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(13):3134. doi:10.3390/cancers13133134

Wierda WG, Allan JN, Siddiqi T, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax for first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: primary analysis results from the minimal residual disease cohort of the randomized phase II CAPTIVATE study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(34):3853-3865. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.00807