Oncology

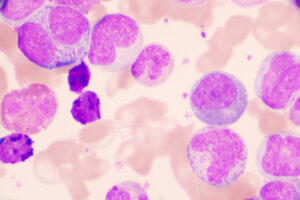

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Genetic Risk Factors in Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Effect on Treatment Selection

Overview

Genetic testing is used to identify patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who are poor candidates for conventional chemoimmunotherapy. However, the effectiveness of novel targeted therapies for the treatment of patients with mutations diminish the importance of such testing.

“In general, the more effective the therapy, the less important the conventional prognostic factors.”

Expert Commentary

Bruce D. Cheson, MD, FACP, FAAAS, FASCO

|

|

|

Genetic testing is used to identify patients who are poor candidates for conventional chemoimmunotherapy. Conventional fluorescence in situ hybridization can identify whether specific genetic abnormalities (eg, 17p deletion [del(17p)], 13q deletion) are present, while next-generation assays provide a deeper analysis of mutation status. In general, the more effective the therapy, the less important the conventional prognostic factors. For example, the long-term follow-up of patients treated with ibrutinib has shown that those with previously recognized prognostic factors (eg, IGHV mutational status, 11q deletion [del(11q)], complex karyotype) respond quite well despite having those factors. Even patients with del(17p) have marked improvement with ibrutinib, although not to the point where they are comparable to those without del(17p). The patients we see are generally well educated about their markers. So if, for example, they ask me about their del(11q), I explain that, although they have this prognostic factor, it does not seem to have as much of an impact in the era of novel therapies as it did previously and it will not influence our choice of therapy, as ibrutinib will work regardless of this risk factor. These novel therapies can also be an appropriate choice because older patients do not tolerate fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR). Notably, a randomized phase 3 trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group- American College of Radiology Imaging Network (EGOG-ACRIN) Cancer Research Group presented by Shanafelt et al at the 60th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting & Exposition in 2018 found that ibrutinib plus rituximab (IR) was superior to FCR with respect to progression-free and overall survival in patients with previously untreated CLL aged 70 years or younger. Further, researchers reported that the findings were not much different in patients who were mutated. FCR is also associated with a higher risk of serious infection compared with a regimen such as bendamustine plus rituximab (BR), as demonstrated in the CLL10 trial. Thus, BR is preferred over FCR, particularly in the elderly patient population. We also now have the Alliance North American Intergroup Study in which patients aged 65 years or older were randomized to ibrutinib, IR, or BR. Both ibrutinib arms were superior to BR. While toxicities were increased in the IR arm, the overall outcome was better compared with BR. The results solidified the role of nonchemotherapy in older patients and underscore the fact that we are rapidly moving toward a chemo-free world for patients with CLL. |

|

References

Eichhorst B, Fins AM, Bahlo J, et al; German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG). First-line chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine and rituximab versus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL10): an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncology. 2016;17:928-942.

Mato A, Nabhan C, Kay NE, et al. Prognostic testing patterns and outcomes of chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients stratified by fluorescence in situ hybridization/cytogenetics: a real-world clinical experience in the Connect CLL Registry. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18(2):114-124.e2.

O’Brien S, Furman RR, Coutre S, et al. Single-agent ibrutinib in treatment-naïve and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a 5-year experience. Blood. 2018;131(17):1910-1919.

Shanafelt TD, Wang V, Kay NE, et al. A randomized phase III study of ibrutinib (PCl-32765)-based therapy vs. standard fludarabine, cyclosphosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) chemoimmunotherapy in untreated younger patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): a trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E1912). Late-breaking abstract-4. Abstract presented at: 60th ASH Annual Meeting & Exposition; December 1-4, 2018; San Diego, CA.

Thompson PA, Tam CS, O’Brien SM, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab treatment achieves long-term disease-free survival in IGHV-mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(3):303-309.

Woyach JA, RUppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib alone or in combination with rituximab produces superior progression free survival (PFS) compared with bendamustine plus rituximab in untreated older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): results of the Alliance North American Intergroup study A041202. Abstract 6. Abstract presented at: 60th ASH Annual Meeting & Exposition; December 1-4, 2018; San Diego, CA.