Oncology

Endometrial Cancer

Predictors of Long-term Survival in Endometrial Cancer

Long-term survival in patients with endometrial cancer has increased with our understanding of the disease and its subtypes. Understanding predictive factors for survival in patients with endometrial cancer can help clinicians match each patient with the best treatment option.

I think that the best predictor of long-term survival for endometrial cancer is having cancer small enough that it can be removed with surgery. Other predictors are a little more encouraging, particularly immune markers for using immunotherapy, as those patients tend to do better, as do patients with well-differentiated tumors, particularly those that are expressing estrogen and progesterone receptors.

We also have a molecular classification strategy for endometrial cancer. As a result of The Cancer Genome Atlas program, we were able to identify a small group of patients who do very well (ie, patients with POLE mutations). These individuals tend to have very good outcomes and either do not need further therapy or respond very well to therapies. We are now contemplating therapy de-escalation for these patients because they may not need chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Tumor staging at the time of diagnosis strongly correlates with long-term survival in patients with endometrial cancer. Patients with stage I disease generally do better than patients with stage II disease, stage II than stage III, and stage III than stage IV. In general, we are able to cure the vast majority of patients who are diagnosed with stage I disease, even when they have a high-risk histology. As you go up in stage from stage II to IV, however, there are incremental increases in adverse outcomes and reduced survival.

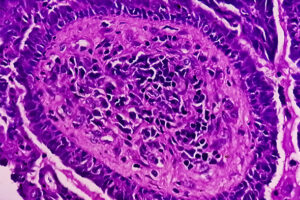

The histologic type of endometrial cancer is also related to survival. Patients with endometrioid tumors generally have the best survival because their disease tends to be low grade and tends to behave in an indolent fashion. Patients with carcinosarcoma, serous carcinoma, or clear-cell carcinoma tend to have high-grade cancers, a higher propensity for recurrence, and shorter progression-free survival.

The molecular classification is also relevant. POLE ultramutated endometrial cancers tend to have an excellent prognosis. Even when those patients have advanced disease at diagnosis, the expectation is that they are going to live a very long time. In contrast, those whose disease is serous like, TP53 abnormal, and copy number high tend to not do very well, with an approximately 30% risk of recurrence. At the time of recurrence, you can push back on the cancer, but the fatality rate remains very high. The prognosis for patients with hypermutated, microsatellite instability–high, and copy number–low disease tends to be between the POLE ultramutated group and the copy number–high group.

Unfortunately, what also matters to cancer treatment and survival are the patient’s preexisting comorbidities. Individuals with more comorbid disorders have worse prognoses because the cancer represents an additional insult on a body that already has a lot of problems to deal with. A patient’s survival can be compromised because they do not have as much in reserve to deal with the cancer insult and all of the side effects of the cancer treatment. Additionally, obesity remains relevant even after initial treatment. In patients who remain obese, the risk of recurrence is higher, so, therefore, survival is more compromised than in patients with a normal body weight or who managed to lose excess weight.

One disappointing thing for someone who treats women with endometrial cancer is that, overall, the incidence continues to increase, along with mortality. As someone who takes care of women with endometrial cancer and does clinical trials, I think that we definitely need to do better.

There are obvious factors that correlate with prognosis, including high-risk histology, TP53-mutant tumors, and advanced stage. We molecularly characterize tumors, and that is going to be considered, along with staging, to identify better predictors of long-term survival and to choose therapy for each patient’s specific tumor, instead of cycling through a sequential line of second-line therapies.

What is interesting to me is that a lot of the screening and prevention efforts for endometrial cancer focus on obesity and diabetes, even though patients with those comorbidities tend to develop lower-risk endometrial cancers. I am curious whether we are focusing on prevention in the right patient populations for us to impact long-term survival. How do we screen for or prevent the higher-risk histology? Is there something that we are missing?

Based on epidemiology studies, we know that higher-risk and more aggressive subtypes of endometrial cancer impact underrepresented minorities, especially patients who may not have good access to care. We need to see what we can do to help identify, screen, and prevent these high-risk histologies. I think that this is the way we can potentially impact long-term survival, but it is obviously a difficult thing to do.

Cosgrove CM, Tritchler DL, Cohn DE, et al. An NRG Oncology/GOG study of molecular classification for risk prediction in endometrioid endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148(1):174-180. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.10.037

Feinberg J, Albright B, Black J, et al. Ten-year comparison study of type 1 and 2 endometrial cancers: risk factors and outcomes. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2019;84(3):290-297. doi:10.1159/000493132

Horeweg N, Nout RA, Jürgenliemk-Schulz IM, et al; PORTEC Study Group. Molecular classification predicts response to radiotherapy in the randomized PORTEC-1 and PORTEC-2 trials for early-stage endometroid endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(27):4369-4380. doi:10.1200/JCO.23.00062

Jumaah AS, Al-Haddad HS, McAllister KA, Yasseen AA. The clinicopathology and survival characteristics of patients with POLE proofreading mutations in endometrial carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0263585. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0263585

Karpel H, Slomovitz B, Coleman RL, Pothuri B. Biomarker-driven therapy in endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023;33(3):343-350. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-003676

Laskov I, Zilberman A, Maltz-Yacobi L, et al. Effect of BMI change on recurrence risk in patients with endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023;33(5):713-718. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2022-004245

Liu L, Habeshian TS, Zhang J, et al. Differential trends in rising endometrial cancer incidence by age, race, and ethnicity. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2023;7(1):pkad001. doi:10.1093/jncics/pkad001

McAlpine J, Leon-Castillo A, Bosse T. The rise of a novel classification system for endometrial carcinoma; integration of molecular subclasses. J Pathol. 2018;244(5):538-549. doi:10.1002/path.5034

Ouldamer L, Bendifallah S, Body G, et al. Predicting poor prognosis recurrence in women with endometrial cancer: a nomogram developed by the FRANCOGYN study group. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(11):1296-1303. doi:10.1038/bjc.2016.337

Siegenthaler F, Lindemann K, Epstein E, et al. Time to first recurrence, pattern of recurrence, and survival after recurrence in endometrial cancer according to the molecular classification. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;165(2):230-238. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.02.024

Somasegar S, Bashi A, Lang SM, et al. Trends in uterine cancer mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;142(4):978-986. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005321

Vrede SW, van Weekden WJ, Visser NCM, et al. Immunohistochemical biomarkers are prognostic relevant in addition to the ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO risk classification in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;161(3):787-794. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.03.031