Oncology

Endometrial Cancer

Immunotherapy in Endometrial Cancer: Current Progress and Future Directions

Overview

Anti–PD-1 therapies are improving survival outcomes for many patients with advanced and recurrent microsatellite instability–high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair–deficient (dMMR) endometrial cancer. Ongoing trials seek to identify additional groups of patients who may benefit from immunotherapy.

How has the role of immune checkpoint inhibition been developing, and what might the future hold for patients with endometrial cancer?

David Scott Miller, MD, FACOG, FACS

|

|

“Probably the biggest advance that has occurred recently stems from the reports from the NRG-GY018 and the RUBY trials (ie, the recognition that the addition of anti–PD-1 therapy to standard chemotherapy results in significantly longer PFS than chemotherapy alone).”

Incorporating immunotherapy into our treatment strategies is one of the more exciting areas in endometrial cancer, particularly as it relates to patients with advanced disease. First, we had the US Food and Drug administration (FDA) approval of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced dMMR/MSI-H tumors. The dMMR/MSI-H status is used to identify individuals who may benefit from immune checkpoint inhibition based on the mutational burden and the propensity for neoantigen formation. We have seen some significant improvements in response rates with this approach, as well as very durable responses. Subsequently, we found that we can add lenvatinib, a multitargeted kinase inhibitor with antiangiogenic properties, to pembrolizumab and achieve responses to immunotherapy that may extend even to patients with mismatch repair–proficient (pMMR) disease.

Probably the biggest advance that has occurred recently stems from the reports from the NRG-GY018 and the RUBY trials (ie, the recognition that the addition of anti–PD-1 therapy to standard chemotherapy results in significantly longer progression-free survival [PFS] than chemotherapy alone). Both trials enrolled patients with advanced endometrial cancer and included both those with dMMR and pMMR status. NRG-GY018 added pembrolizumab to carboplatin and paclitaxel, which significantly improved PFS. The overall survival data are still a little immature, but early results appear very encouraging. Then, we had the RUBY trial, which added the anti–PD-1 therapy dostarlimab to carboplatin and paclitaxel. Patients showed a significant improvement in PFS with the addition of dostarlimab, as well as a significant increase in duration of response.

Where are we going next with immunotherapy? Well, we want to see if we can extend these benefits to more patients, including in groups of patients with earlier-stage disease. For example, there is a trial evaluating adjuvant checkpoint blockade with dostarlimab plus radiation in locally advanced dMMR/MSI-H endometrial cancer (NCT04774419). A number of other trials are ongoing, and we look forward to seeing those results.

Pamela T. Soliman, MD, MPH

|

|

“Clinically, we see that many individuals who receive these agents not only do well but also have prolonged responses. So, these therapies are very exciting.”

Immunotherapy has really been a game changer across several malignancies. In endometrial cancer, dMMR/MSI-H tumors account for 25% to 30% of the total, and both pembrolizumab and dostarlimab have FDA-approved indications for the treatment of advanced dMMR/MSI-H tumors. Clinically, we see that many individuals who receive these agents not only do well but also have prolonged responses. So, these therapies are very exciting.

Early-phase studies evaluating anti–PD-1 therapy in combinations showed very promising results. In fact, results of the phase 1B/2 trials of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab were better than expected, so I think that we were curious to see whether those response rates would hold up with time and in the setting of a larger phase 3 trial—and they have. The combination of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab received rapid FDA approval in a patient population for whom carboplatin and paclitaxel had really been the only effective therapy.

As Dr Miller noted, this year’s reports from NRG-GY018 and RUBY were impressive. Adding immunotherapy to frontline therapy not only increased the response rates but also significantly reduced the risk of cancer progression. Data still need to mature, but there has been a clear benefit from adding anti–PD-1 therapy to frontline chemotherapy in patients with dMMR/MSI-H advanced disease. Contemporary guidelines were prompt to include updates in light of these data. Although it is possible that things will shift with time as we learn more about the optimal use of these immunotherapies, these were both certainly practice-changing studies.

Looking to the future, studies are also needed to determine whether patients with newly diagnosed, advanced dMMR endometrial cancer can go straight to immunotherapy instead of going to chemotherapy first.

Alexander B. Olawaiye, MD, FRCOG, FACOG, FACS

|

|

“These 2 groups (ie, the POLE ultra-mutated group and the dMMR/MSI-H group) are the primary groups of interest for immune-targeted therapy right now. And this has implications for the future in terms of patient selection.”

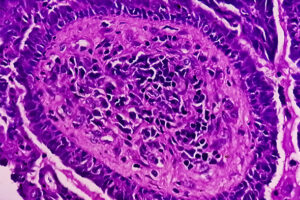

Immunotherapy in endometrial cancer really has at its origins the application of new genomic discoveries to the treatment of cancer. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), a joint effort between the National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute, is a remarkable program that began in 2006. Sequencing data from this initiative became available in the early 2010s for a number of cancers, and, subsequently, a group of brilliant scientists essentially used TCGA findings to characterize endometrial cancer based on genomic abnormalities. TCGA classification thus forms the basis for what we now refer to popularly as the molecular classification of endometrial cancer. The group identified 4 distinct prognostic subtypes: DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) ultra-mutated, MSI-H, copy-number low, and copy-number high.

Patients in the first group, the POLE ultra-mutated group, have an excellent prognosis. What is more, based on the biology of this group, they are expected to be super-responders to immunotherapy. The second group is the MSI-H group, and this is also the so-called dMMR group. This is the group to which individuals with Lynch syndrome belong. Patients in this group are also expected to be super-responders to immunotherapy. These 2 groups (ie, the POLE ultra-mutated group and the dMMR/MSI-H group) are the primary groups of interest for immune-targeted therapy right now. And this has implications for the future in terms of patient selection. In the copy-number low group, the value of immunotherapy is unclear. The final group, the copy-number high group, which shows near universal TP53 mutation, is the group with the worst prognosis and a low likelihood of response to immunotherapy.

In NRG-GY018, pembrolizumab improved PFS, with the greatest benefit reported in patients with dMMR status. In RUBY, dostarlimab benefited patients with diverse profiles, including those with the rare diagnosis of carcinosarcoma, which is not usually treated with immunotherapy. Response rates were high in patients with dMMR/MSI-H tumors, and both PFS and overall survival were significantly improved.

References

Barroso-Sousa R, Ott PA. PD-1 inhibitors in endometrial cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(63):106169-106170. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.22583

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Kandoth C, Schultz N, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma [published correction appears in Nature. 2013;500(7461):242]. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67-73. doi:10.1038/nature12113

ClinicalTrials.gov. Radiation and dostarlimab in people with endometrial cancer after they receive surgery. Updated November 16, 2022. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04774419

Eskander RN, Sill MW, Beffa L, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in advanced endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(23):2159-2170. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2302312

Hom-Tedla M, Eskander RN. Immunotherapy treatment landscape for patients with endometrial cancer: current evidence and future opportunities. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2023;21(1):27-34.

Maio M, Ascierto PA, Manzyuk L, et al. Pembrolizumab in microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair deficient cancers: updated analysis from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(9):929-938. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2022.05.519

Makker V, Colombo N, Casado Herráez A, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in previously treated advanced endometrial cancer: updated efficacy and safety from the randomized phase III study 309/KEYNOTE-775. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16):2904-2910. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.02152

Makker V, Colombo N, Casado Herráez A, et al; Study 309–KEYNOTE-775 Investigators. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for advanced endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(5):437-448. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2108330

Mirza MR, Chase DM, Slomovitz BM, et al; RUBY Investigators. Dostarlimab for primary advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(23):2145-2158. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2216334

Slomovitz BM, Cibula D, Simsek T, et al. KEYNOTE-C93/GOG-3064/ENGOT-en15: a phase 3, randomized, open-label study of first-line pembrolizumab versus platinum-doublet chemotherapy in mismatch repair deficient advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 16):TPS5623. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.TPS5623

Talhouk A, McConechy MK, Leung S, et al. A clinically applicable molecular-based classification for endometrial cancers. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(2):299-310. doi:10.1038/bjc.2015.190